Tennessee is 67-70 in the last 11 years, a longer sub-.500 run in the modern era than we can find for any of the other 15 winningest programs in college football history. A more concrete way to look at it: the Vols haven’t finished a season in the AP Top 20 since 2007, sneaking in at #22 after bowl wins in 2015 and 2016. That 11-year drought is also the longest on record in the modern era for any of the 15 winningest programs (via Wikipedia):

| Team | Years w/o Top 20 Finish | Seasons |

| Tennessee | 11 | 2008-18 |

| Nebraska | 8 | 2011-18 |

| Florida | 8 | 1975-82 |

| Michigan | 7 | 1957-63 |

| LSU | 7 | 1989-95 |

| Notre Dame | 6 | 1981-86 |

| Oklahoma | 6 | 1994-99 |

| Texas | 6 | 1984-99 |

| Southern Cal | 6 | 1996-2001 |

| Penn State | 6 | 2010-15 |

| Miami | 6 | 2010-15 |

| Ohio State | 5 | 1987-91 |

| Alabama | 5 | 1954-58 |

| Florida State | 5 | 2005-09 |

| Georgia | 4 | 1993-96 |

| Auburn | 4 | 1976-79 |

The second-longest drought among these teams isn’t actually Nebraska’s current stretch: it’s also Tennessee, 10 years from 1975-84. So good news: the Vols have made this climb before. What Jeremy Pruitt is trying to dig out of is most similar to the challenge Johnny Majors faced in the early 1980’s.

When Doug Dickey left for Florida in 1969, Bill Battle took over and led the Vols to an 11-1 finish in 1970, the highest-rated Vol squad in estimated S&P+ of the last 50 years. Tennessee went 10-2 in 1971, then 25-9-2 in Condredge Holloway’s three seasons at quarterback. The Vols finished in the Top 20 in each of Battle’s first five seasons.

But the Vols went 7-5 in 1975 and 6-5 in 1976, ran their losing streak to Alabama to six straight, and Battle was replaced with native son Johnny Majors fresh off his national championship at Pittsburgh.

Majors’ first four Tennessee teams had a combined record of 21-23-1 and only one bowl appearance. If you’re just looking at wins and losses, his fifth team in 1981 appears to have broken the trend with an 8-4 season. But estimated S&P+ rates that team as the second-worst of the last 50 years behind 2017. Here’s a closer look at Majors’ first five seasons:

| W | L | T | Pts For | Pts Against | vs Ranked | One Poss. |

| 1977 | 4 | 7 | 0 | 229 | 229 | 0-3 | 1-2 |

| 1978 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 251 | 209 | 0-3 | 0-0-1 |

| 1979 | 7 | 5 | 0 | 311 | 235 | 1-2 | 1-2 |

| 1980 | 5 | 6 | 0 | 256 | 189 | 1-4 | 0-3 |

| 1981 | 8 | 4 | 0 | 244 | 265 | 0-3 | 6-0 |

Going 6-0 in one possession games (including 24-21 over Wichita State and 38-34 vs Vanderbilt) is a great way to mask a negative point differential. In reality, these first five years should be grouped together as the downturn before we start talking about Tennessee’s slow and steady ascent.

If 1981 was a relative bottom from a competitiveness standpoint, the Vols made incremental progress every year from there. This too didn’t always show up in the win column, but you can see it in the point differential:

| W | L | T | Pts For | Pts Against | vs Ranked | One Poss. |

| 1982 | 6 | 5 | 1 | 281 | 239 | 1-0-1 | 3-3-1 |

| 1983 | 9 | 3 | 0 | 282 | 165 | 2-2 | 3-1 |

| 1984 | 7 | 4 | 1 | 327 | 276 | 0-3 | 4-2-1 |

(On the strength of the 1983 defense: see White, Reggie.)

In estimated S&P+ percentile, the Vols went from 35.63 in 1981 to 55.46 to 80.07 to 87.26 in 1984. After a 1-2 start in 1983 with losses to #10 Pittsburgh and #11 Auburn, the Vols won eight of their last nine games and just missed running the table in a 13-10 loss to Ole Miss. Three of Tennessee’s four losses in 1984 came to ranked opponents, the fourth to a Kentucky squad that finished the season ranked.

Progress was there, though it might’ve been harder to see in the moment. I was born in 1981, so I can’t really speak to the personal experience of any of these years. But I can guarantee you what made everything better for Johnny Majors was beating Alabama.

The Tide won 11 straight from 1971-81. But Tennessee upset the #2 Tide 35-28 in 1982, Bear Bryant’s final season. In 1983 it was 41-34 over #11 Alabama in Birmingham thanks to a Johnnie Jones run. And in 1984 the Vols erased a 14-point deficit in the final nine minutes to win 28-27 in Knoxville.

When you get three straight against your biggest rival, everything else matters a little less. Consider how many Butch Jones sins are forgiven if the Vols beat Florida in 2014, 2015, and 2016 (and 2017, for that matter).

After going 29-27-1 (.518) from 1977-81, the Vols went 22-12-2 (.688) the next three seasons. Getting back to being a team that averaged 7-8 wins in an 11-game regular season was a big step. But at this point, the Vols had still gone 10 years without finishing in the AP Top 20.

The breakthrough came in 1985:

| W | L | T | Pts For | Pts Against | vs Ranked | One Poss. |

| 1985 | 9 | 1 | 2 | 325 | 140 | 3-1-1 | 2-1-2 |

Not only did the Vols get four straight against Alabama, they dominated Bo Jackson and #1 Auburn 38-20. The Vols won the SEC and, of course, beat #2 Miami 35-7 in the Sugar Bowl, putting an emphatic end to a decade away from the national stage with a top five finish.

It took a little more time for that kind of finish to become commonplace. The Vols yo-yoed with a 7-5 finish in 1986, 10-2-1 ranked 14th in 1987, and 5-6 in 1988. But from there, Tennessee entered its longest stretch of sustained excellence: 129-29-2 from 1989-2001, a .813 winning percentage that was best in the SEC for those 13 years. With the exception of an obvious rebuild in 2000, the Vols played at the 88th percentile or better in estimated S&P+ for that entire stretch. The Vols played at the 87th percentile or below every year from 1975-84.

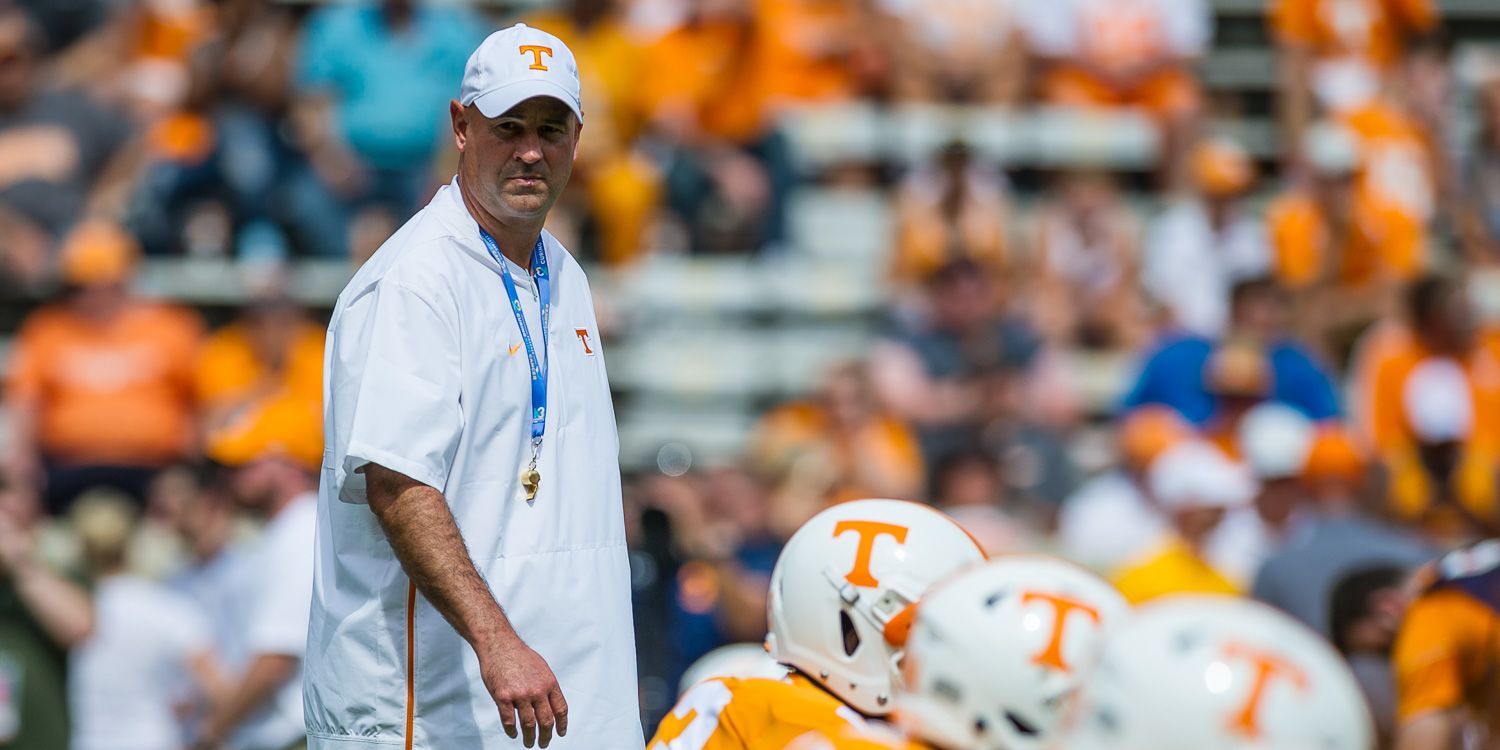

After last season, Tennessee’s drought in the postseason AP Top 20 reached 11 years, one more than that 1975-84 downturn. To be sure, the Vols seem farther away from a championship breakthrough in 2019 than they were in 1984. But Jeremy Pruitt and the Vols are already following that early 80’s blueprint:

| W | L | T | Pts For | Pts Against | vs Ranked | One Poss. |

| 2017 | 4 | 8 | 0 | 238 | 349 | 0-4 | 2-3 |

| 2018 | 5 | 7 | 0 | 273 | 335 | 2-3 | 1-1 |

2017 and 1981 are the two lowest seasons of the last 50 years in estimated S&P+ percentile; 2017 is far worse at 17.4%, but remember that 1981 team won six one-possession games. They’re not so dissimilar considering Butch Jones’ last team lost on the final play against Florida, South Carolina, and Kentucky.

So we’ve already seen the Vols make progress from the bottom. But like those early Majors teams, Tennessee had a hard time just getting in one-possession games last year. The trap Butch Jones’ teams fell into was believing being close was a good thing, playing far too many one-possession and even final-play games to escape a treadmill that topped out at 8-4. But for Jeremy Pruitt in year two, courting heartbreak via close games would look like progress. It can’t be confused for the destination – Pruitt’s time at Florida State and Alabama blowing teams up should assure he’s already learned that lesson – but it’s a step the Vols can take along the way.

Being gone longer than any other blue-blood program should remind us of the task at hand. But Tennessee’s climb in the early 1980’s – slow but steady – should remind us that such a feat can be accomplished at this university. It may not happen as fast as any of us want, but progress is both readily available and already underway. Keep recruiting and developing well. Get competitive but don’t settle for living there. Make 8-4 an average expectation and not something you have to rebuild after. And, you know, beat Florida.

Tennessee has a long way to go, perhaps longer than any other program with our past can appreciate. But the Vols have made this climb before, and came out of it with their very best days ahead of them. I’m eager to see what the next step will look like this fall.